Confronting & Teaching Hard History

Episode 5 from the Educational Equity Emancipation podcast.

(This transcript has edited for clarity and readability.)

Hey there equity warriors. I'm glad we are together again today.

So much to share. So much to share. And hopefully, you won't get discouraged as I tell you today's topic. Stay with me, please. This is going to be a fun one as we chat about confronting and teaching hard history.

So, although controversial, there's this guy whose name was Mark Twain. Maybe you've heard of him. Stay with me. Mark Twain wrote,

"The very ink with which history is written is merely fluid prejudice."

Is that not cool, or what?

A few weeks ago, when it first came out, I went to see The Woman King. And there's this secondary character, I guess, like a supporting actress, I don't know. But besides Viola Davis (because we all know Viola), the secondary character: her name is Nami. And she's given this rope as the first weapon she's going to train with. Now Nami has this huge personality, and she's looking for the spears and the guns and the big stuff so that she can…. She's got a little violent streak in her.

So, she looks at this rope. And the expression on her face is like this mix of disgust and bewilderment, and she mumbles underneath her breath, "A rope is not a weapon."

Now, those of us who are teachers, like, we could hear that come out of the mouth of one child amongst 30 or 40 when everybody's talking. Right? So you can imagine what happens! She wants to get her hands on the big stuff, these fierce-looking machetes. And by the end of the movie, if you haven't seen it yet, you'll know just how Nami learns to use that rope as a formidable weapon.

I thought about that. And I thought about us. And I thought, as equity warriors, we need weapons too. And our weapons are never going to be the fierce-looking machetes. They're going to be more like these little, tiny ropes because our greatest weapon is knowledge. Its facts. And it's data.

By the end of this episode, you're going to learn just how information can be a weapon in your arsenal. So, I want you to think about these things:

Let's think about the 1619 Project, slavery, the Indian Removal Act, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and the Land Ordinance Act that allowed white people to claim free soil. Put air quotes around that "free soil," while Blacks and Indigenous people had to purchase that same soil. And it wasn't anybody's soil to give away except for the Indigenous people who had occupied it forever. But claimed by colonizers, white colonizers, here in the U.S.

Oh, and then there's this one. We all know this one: CRT. Those horrible three words.

So, I want to talk about the importance of teaching hard history with you today as simply more like providing equitable education for all children. Because no matter what many people would have us believe, there is so much diversity in that hard history of America.

And I'm not gonna talk global history. I mean, I could, but that's not the point here. We're working on this country and our school systems. Right? Our organizations.

Now... history. If anybody ever asked me, history was always my favorite subject in school. And I don't know why. Because, for one, I never liked the whole memorizing dates and chronology thing. It never helped me to understand what order things happened. Right? Didn't make sense to me. But I still loved history. And I guess what I loved were the stories and the connection.

I never stuck with just what the history was that I was being taught in school. I was an avid reader. I was a bookworm. I was a nerd. I was quiet. I was shy. I know, shocker. Hard to believe. But then, when I taught history (because my first credential was social sciences), I taught U.S. history at the high school level. I refused to teach it chronologically. Instead, I taught it thematically: in themes that showed contrast. Right?

One of the themes I taught was War and Peace. One theme I taught was Poverty and Prosperity. And then there was Rights and Responsibilities and Immigration and Emigration. So, immigration with an "I" and then immigration with an "E." And then, for the life of me, it escapes me what that fifth theme was. But I remember teaching five themes. I could go back through my scrapbook and look at pictures of my classrooms. They'd be on the walls. But anyhow... Those things, those stories, those contrasts, that's how we make meaning, right?

Because it's that ability to start to connect past events to present events, it helps us frame that larger historical context. And it helps us with problem-solving. Here's a thought. We probably heard it misquoted. The actual words are,

> “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

And right now, there's a whole lot of people out there working really, really hard to make sure that we not only not learn the past, but what we learn of the past are only the stories they want us to know.

Remember, the Alamo. Remember the Boston Tea Party. Oh, but let's forget about slavery. So, here's the story, the real story:

America's story we're teaching about our Indigenous brothers and sisters is a story that should have a chapter from the 18th century. I know, I hate the dates. But this is sort of important for context. I'm not going to give you a year, 18th century. Right?

Several states and the federal government itself offered cash for the scalps of Native Americans.

And people today don't understand why the term "redskin" is offensive. That's the origin.

There should be another chapter, a chapter that focuses on the Organic Act: the Organic Act of New Mexico. And that's when they granted full citizenship to free whites and Mexican citizens, as covered by the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

And in that same act, it asserted that no Indian could be a citizen.

It was their land!

Here's another chapter. How about a chapter that highlights how, in the late mid-1800s, there was a California law that defined an Indian as having one-half Indian blood? It allowed white men to force Indians into unpaid labor, essentially, slavery.

Slavery for vagrancy.

So, if they didn't have a job, they were going to make them have a job. But only Indians. And I hate that term. I use it in a historical context. And I try not to, but our Indigenous brothers and sisters, from whatever tribe and all tribes, in California.

So, the same law, same place, California. They had that law that was then revised, so instead of one-half (and, you know, Indian is the word used in the statute), instead of one-half Indian blood, if they were one-fourth, one-fourth Native American! that then they could be forced into slavery, essentially.

And then there were all these other laws that said what they could and could not do if they had one-fourth Native American blood.

And that's where the term half breeds came from. This country's laws.

So, there's another unit in this story, in this history, in America's story. And this, of course, would be the unit on our Black brothers and sisters, those of us with African ancestry. So, 1619, right? We're all learning, or have learned, that's when a Dutch ship brought roughly 20 Africans into Jamestown, Virginia.

The beginning of the story of slavery, a story that makes us question why in this country and only in this country... And you know what, I'm gonna go down the rabbit hole here for a second.

This nonsense about "Africans sold their own people into slavery..." Yes. But if you look at the history of slavery, in pretty much every other nation, it was more like indentured servitude. And the African tribes, when they did take people into slavery as they had it there, it was because of a war between two tribes. And those people that they took in became members of their tribe. They became full citizens of that tribe. It wasn't an inheritable state like it was here.

So here in the United States: unique American exceptionalism.

If your mother was a slave, you were going to be a slave. If your mother was a slave, you were going to be a slave: generation after generation after generation. And you know why?

Because it allowed white slave owners to rape their Black slaves and create more slaves for their own wealth. And that act broke with hundreds, or maybe thousands, definitely hundreds of years of what was the English legal tradition where whatever the Father was would dictate what the child would become.

This is the story that tells how and why African slaves were bred like cattle.

This is the story of those horrors of raping enslaved women without consequence to one's name or status.

And I think about that, in the context of today, where we've got these states passing laws with… with those anti-abortion laws with no exception for rape. Hmm, where'd that idea come from? Coming out of that rabbit hole. That's not for today. But history - past and present. Start making those connections.

My Latino brothers and sisters, your story is very interesting when we look at American history. So, I'm going to focus on just one thing, and that's the Texas Annexation Agreement. And when we look at, when we learn that story, we should be learning vocabulary terms. I'm going to give you one, "white Mexican."

White Mexican.

Look it up for yourself. Because that is what allowed those people who were Mexicans - now keep in mind, Texas was part of Mexico, okay, there was this war... But allowed Mexicans who appeared white, who looked like they were white, to be considered white.

When I learned this, I had this huge aha moment. Wait a minute, we just had this conversation, or I just had that conversation a few weeks ago with a group. And we were talking about how on, you know, those forms where you check the box?

You know. Are you Hispanic? Non-Hispanic?

And then, you check a second box that says, "Choose one: White, Black, Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, Indigenous (however it's worded), and then two or more races.

What do you check if you're Mexican, Guatemalan, or Honduran from South America from Central America? Are you White, Black, Asian, Native American, or two or more races? White Mexican, from our own legal system. So forced to identify themselves as white and Hispanic because the others don't really seem to apply. But anyhow.

America's story about our Asian brothers and sisters: The Foreign Miners Act, Chinese Exclusion Act. So mid-1800s. Again, it's not that long ago. It's 122 years roughly. One hundred, no 170 years. I can't do math. And, well, I can do math. I can do math. It's just not my thing. So yeah, 170 years ago in California, as well. And if you haven't heard it, I think it's like the second episode where I talk about a slave auction and a high school football team locker room. Go back and listen to that one.

But there was this thing the California Legislature passed; this thing called The Foreign Miners Tax. And so, any non-US-born miners had to pay a monthly $20 tax.

This is the first piece of anti-Chinese Legislation in California.

Forty-niners, not the football team, but this is where they got the name. The big Gold Rush was 1849. Right? So as the Chinese were coming in and doing what everybody else was doing, as they came into California to go up into the hills pan or blast, or you know, do whatever it was they were doing in search of gold.

It was okay if you were white. But if you were Chinese, you were going to pay $20 a month. Twenty dollars was a whole lot of money back then.

And the story goes on. If I had all day, I could go all day. But if we study the Constitution, we start to learn about, really learn, not know it's in there, but really learn about the Three-Fifths Compromise: Article One, Section Two.

And that's the piece that said that Black people were only going to be counted as three-fifths of a person. And we really get pissed off about the three-fifths, and we should. It's wrong. But you know what else is wrong? The fact that Indigenous Americans, the people whose country this was, whose land it was, they weren't counted at all.

They were "non-people," as far as the Constitution was concerned. And this situation didn't get straight until after the Civil War with the passage of the 14th Amendment. When we start looking at the history of the laws in this nation, and we start learning about the Slave Codes, and again, the little bit of a misnomer. Yes, we call them the Slave Codes. But do you know who was included in that? Not just Black folks. But our Indigenous Mulattos. Muslim North Africans they're referred to as Mores.

All of us: Black, Indigenous, Mulatto, Muslim, we were all considered slaves. Even if we were free.

None of those groups of people, none of us, could marry a white person.

And these laws legalized the killing of Black people whenever they resisted the order of a white person. Didn't have to be their boss, any white person on the street. And this is where, excuse me, not here. But it goes as far back as the pre-1700s, like 1690 or 1691. Somewhere around there, pre-1700, you'll find the first legal use of the word "white" as identifying Europeans by the perceived color of their skin.

And again, the story goes on and on and on and on. So, I'm gonna give you another word: holocaust.

And I know what you're thinking. You're thinking about the Holocaust, capital H. I'm not talking about that one. I'm talking lowercase h, holocaust. Look it up in the dictionary.

It's defined as

> destruction or slaughter on a mass scale> .

But those of us, or most of us who went through K-12 in an American public school, probably only learned about the one that first popped into your head: Nazi Germany's holocaust of roughly 6 million Jewish people. Atrocious. Horrific.

And we should learn about it. But what about our own? What about the holocausts and genocides right here in the good old, exceptional USA?

I will say this for Germany: they have gone to great lengths to make sure that the horrors of Nazi Germany and Hitler's final solution are taught to every single child, so they never make the same mistakes!

Again, you can't find a statue of Hitler or any of his cronies. You can't find one of those in Germany! But heaven help you try to take down a Confederate statue here in the good ole U.S. of A. Or try to change the name of a school that was named after a confederate.

I read something a couple of weeks ago that had the number of schools that are still named after Confederates. And people are fighting that it's “our heritage.”

You know what this whole thing is when they don't want to talk about the American holocausts and American genocide? They only want to talk about the stuff that happened on foreign soil? That's kind of like a “Hey! Look over there! Don't look in our own backyard. Look over there. Oh my gosh, isn't that terrible what they're doing?”

So here are the American holocausts. Plural. With an S, holocausts.

Going back to our book that we would write, a story chapter begins with Europeans who landed on North American soil with an Indigenous population. We look north of the Rio Grande because we want to look at what is currently the configuration of the United States, right? Roughly between, and I know this is a big gap in numbers, but the historians haven't quite come to agreement on it. There was no census. But somewhere between 10 and 19 million Indigenous Americans, Native Americans. Six hundred, roughly 600 tribes and equally diverse dialects were here in this country before Europeans got here.

After they got here, in that next chapter, first 200 years: 9 out of 10, nine out of ten, 90% of the Indigenous people were dead.

That was the first holocaust here on U.S. soil. Killed by disease and by violence, some 9 to 17 million people.

Our story in this country is a story of cultural genocide, where language diversity dropped from roughly 600 tribal dialects to less than 30. And tribes today are fighting to keep their languages alive.

It's a story I feel every time I do a workshop activity on identity, and I ask my Indigenous brothers and sisters to stand. Unless I'm on a reservation, or you know, Alaska, New Mexico, it's a little bit of a different story.

The American holocausts. That was our first one. But there are more.

Another American holocaust is about the more than 1.5 million people taken into slavery from Africa who died just in the course of the transatlantic passage. Fourteen percent of those people who were captured never made it to American soil.

Oh, but don't worry. Because you see, those shipping companies who were transporting Africans to be sold into slavery? They had insurance. Thank you, Lloyd's of London. They were insured. So, they were fine.

They didn't care about their lost cargo. They still got paid.

Oh, but let's not talk about reparations, the story of forced removal, or the Indian Removal Act. That act, that piece of American legislation that placed what was left of the 10% of the Indigenous Americans that were left after disease and violence killed everyone else, that put them onto reservations in the most desolate places in America. They're not on prime real estate.

It's the story of more than 4000 members of the Cherokee Nation who died on the Trail of Tears.

Imagine, imagine walking barefoot 1200 miles. Imagine walking from Georgia, North Carolina, Alabama, or Tennessee, to west of the Mississippi, to New Mexico. Because someone wants your land, and we have the... you know, I try not to curse.

We have the audacity to be up in arms about Ukraine. We won't even recognize what we've done to Indigenous people on this soil. But, oh, look at what Russia is doing to Ukraine!

American holocaust.

Seventeenth century. There were indentured white European servants. Most of them, or a good majority of them, were Irish. Half of them died within five years while they were working to secure their freedom in the Chesapeake colonies, Virginia, and Maryland.

But servants cost half as much as slaves. So it was a much more economical investment.

American holocausts.

So the 20th century by itself, right? We can have, we have, multiple chapters just in the 20th century.

We've got the Tulsa race massacre.

We've got the Osage Reign of Terror in Oklahoma.

What is it about Oklahoma?

We have hundreds, hundreds of thousands of civilians that died across Asia at our hands as the U.S. pursued interests in the Philippines and Vietnam.

And we have the ugly, decades-long history of lynchings of Black men across the Southern states.

And now, modern-day lynchings like those we can see in a TikTok video or a Facebook Live. Like we saw George Floyd. We should all - Black, white, brown, Asian, whatever you are - we should all feel guilt and anger. Anguish. Not because we did these things. We didn't personally commit these atrocities. No one's saying we did. But because history is ugly, and it's painful. And we know there can't be winners unless there are losers.

But we have to come to grips. We haven't stood up long enough, loud enough, with enough of an allyship across races built on diversity to make it known, to make the ugly history of this nation be taught.

We haven't gone through the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. (I think those are they, and I think that's in the right order: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance.)

Many of those of us who are marginalized people and many of our allies have made it through those five stages, and we're at acceptance. We're angry. And we want things changed. But we've accepted this is the ugly history of this nation.

It's not resolved, but we get it. We all need to understand it.

What's happening, though, is that people in power, primarily who are white, are in denial and anger. Because to come to grips with it, to come to acceptance with it, means that they have to cede power.

Hard history is called hard history because it's not a fairy tale.

Our books, our lessons, our texts, how we craft our history, lessons in the classroom, should reflect the truth. All of the truth. Warts and all.

Atrocities, hidden embarrassing pieces of history, need to come to light. We need to teach them because teaching them and understanding them is what will change the behavior of people here forward.

So, why don't we do it? Why don't we? You could just say, "ignorance is bliss." Right? Those in power fear that that knowledge will shine a light on their own racist actions that are happening today.

Remember what I said about abortion? With no exception for rape and incest? Think about the history of this nation. Make that connection.

And so, it's so much easier for them to blame teachers for trying to indoctrinate children than to face the truth. They rely on this revised history, this false narrative that there's some horrible boogeyman in our textbooks in our libraries. Honestly, more libraries than our textbooks because, for the most part (apologies to any commercial curriculum people that are on the line who have made changes in their curriculum), for years, the vast majority of what's in an adopted textbook for a state history program is most, more often, or most often whitewashed to such an extreme, just so that the books can be listed. Pass a state textbook committee review. And make the adoption list. And make money. Nothing wrong with making money.

So, in social studies, if we can, we can rely on primary source documents. We can get, we get… There's film. There are letters. There are biographies and autobiographies. There's the law.

Oh, but I'm sorry, my bad. A lot of those even are being banned.

Remember the big bad boogeyman CRT? So, let's go there for a minute because I can't do this and not go down this rabbit hole.

What's the difference between American history and critical race theory? What's the difference?

So, American history is the story of this nation, right? Warts and all. All of the story. Unredacted. Uncensored. That's American history.

Critical Race Theory is a way of analyzing structures, institutional structures, and how those structures impact people, centering race as the primary lens for our understanding and in this context that we're talking about: educational inequities. So, CRT is supposed to help us understand, or CRT does help us understand, why public schools disproportionately suspend and expel students of color. Why?

Why there are Black-White, Brown-White, Indigenous-White, and Southeast Asian-White achievement gaps. And why those gaps are fueled by a provision gap. Because the provision of instruction is disproportionately done by people who don't look like the children in the classrooms.

That's what CRT is supposed to help us do. But if we understand critical race theory, then we're going to see the blinders come off. And we have the ability to look through this lens of equity.

We have a core responsibility. Schools, educators, have a core responsibility to prepare every single child for civic engagement so that they become productive citizens in this country, whether they're a citizen or not, if they're an adult in this country.

So how is this conflation of history and CRT manifesting the most?

Seen a good book ban lately?

I remember when I was in high school, this whole controversy over To Kill a Mockingbird. And so I never read To Kill a Mockingbird when I was in high school; it had been banned. As a new teacher, the book that got banned was The Color Purple.

But then I started to understand why these things were being done. So I got the book. I read it on my own (I think I'd read it before I was a teacher, but…) with greater understanding. So now, more than at any time in American history, there are over 2,500 banned titles!

To Kill a Mockingbird. The Color Purple. Two books. I'm sure there were more.

We have districts now that have banned the Bible. There are more than 5,000 schools (hopefully I have my number straight), 5,000 schools that enroll about 4 million students. They don't serve 4 million students, but they do have an enrollment of roughly 4 million. Four million students. More than 5,000 schools have banned books.

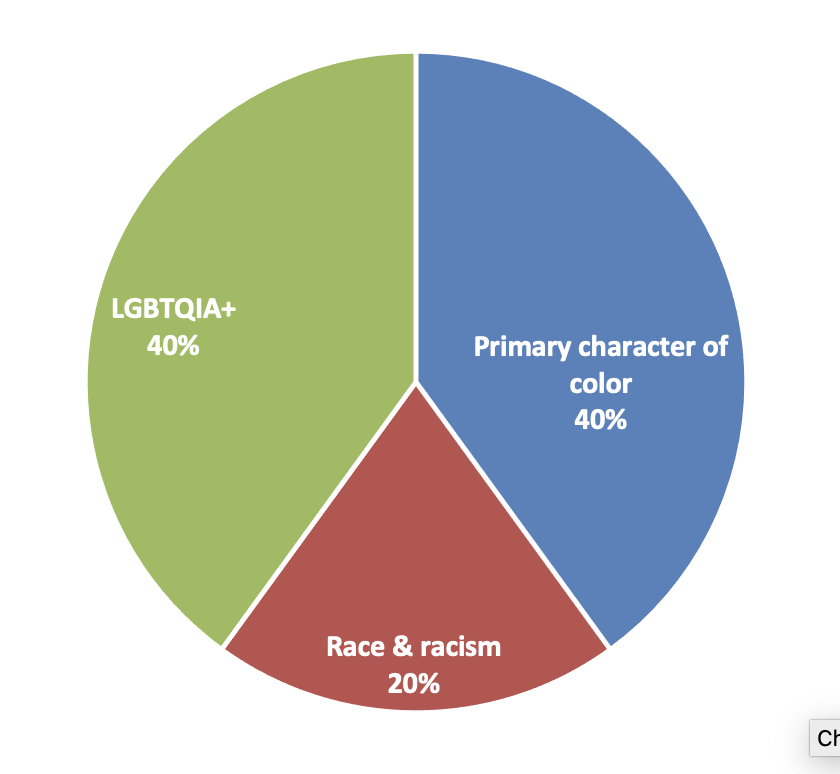

Most of the things that are getting banned now, roughly 40% of the books that are getting banned, have a primary protagonist or a secondary character who is a person of color.

Another 40% is about LGBTQ characters.

And then, the final 20% directly addresses race and racism. So, round math, you see that's not 47.2% or 38.1%: 40/40/20. Take that 40. That's about characters of color.

Take that 20. That's race and racism.

Sixty percent of what we're banning... It's not we. Not we. Sixty percent of what's being banned is about race, racism, and people of color.

Now, the 40%: LGBTQ. So, if you didn't listen to my episode on the four equity indicators, go back and listen to that because it will kind of help where I talk about meritocracy, standards, impartiality, asset allocation. That's power, mastery, and representation.

And so, what we're seeing, as we look at hard history, needing to be taught, but not being taught as content and books are being banned from the classroom is a... I can't even say the word sometimes. They're putting politics into public education.

And equity warriors, people like you and me, we are needed to protect the right to a free appropriate public education. Remember the FAPE? Keyword: appropriate.

This sanitizing history, this removing books that make people uncomfortable, is anti-American, and it's unconstitutional.

Remember our little ropes? These are they.

Silencing teachers and banning books is the antithesis of free speech. Doing this is a violation of the First Amendment right, and the value America has always placed on free speech.

If we dig into the 14th Amendment, there's this thing in there called the Equal Protection Clause, and I would argue that this sanitizing and banning is a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. Equal Protection Clause, by the way, is where Brown versus the Board of Education rests. I would argue, because of that 40% of books that deal with LGBTQ characters, that it's also a violation of Title IX, that protects teachers and students from gender-based discrimination.

What about the civics being taught in your system? So, civics is the study of rights and obligations of citizens and of a society's rights and obligations. Notice the places where civics is being attacked.

If we don't learn our rights, if we don't teach the children what their rights are, those who wish to keep the marginalized and oppressed peoples of this country marginalized and oppressed will win. And we can't let them win.

I'm a huge fan of Proverbs. Some of you may know that from a session you've been in with me, or you've read my book Effecting Change. And there's a West African proverb that says,

> "Until the lion tells the story, the hunter will always be the hero."

Until the lion tells the story, the hunter will always be the hero. If you're an educator or an instructional leader, create lessons in response to the cultures of your students.

Be respectful. Be culturally aware. Avoid tokenism. Use your community resources if you need help. Dig into and rely on those primary source documents. Call attention to the untold and lesser-known stories of marginalized people. You see, there's a reason that slaves weren't allowed to learn to read and write. Because they didn't want us to know the truth. They didn't want us to know our stories. But there's also a tremendous tradition of oral history in the Black and Indigenous populations and probably others that I don't know.

And use the internet. Let's say you've got a group of learners with a language, primary language, or primary culture that you don't know anything about. Ask them to help you or ask them to help search the internet using their primary language to get materials.

Look through these lenses. Master your little robes.

Because when students from all backgrounds, but particularly historically marginalized ones, see their culture, learn their stories, when they are equitably represented in curricula, they start to feel a sense of belonging, and it improves their educational experience. Gandhi said,

> "A small body of determined spirits fired by an unquenchable faith in their mission can alter the course of history."

So, start calling, writing, and tweeting legislators and school board members. Run for school board. Show up at school board meetings. I used to do that at every single school board meeting. Oh Lord, they didn't like it when they saw my name when they pulled the card about who got to speak next.

Let your voice be heard.

Address the Board. Take other equity worries with you. I'll tell you what I used to do. If we had something long that needed to be addressed, we would write it all out. Everybody that went with us as part of the group, I was a PTA president, and so I would call on my team to support us in bringing issues forward; we'd all have a copy. And the first person who got called would start reading. When their two minutes were up, and they turned off the mic, we just marked where that person stopped.

You can do this. There are things you can do. Don't be limited by your two minutes. Get creative.

Take the children. Let them see civics in action. Encourage them to speak.

It's a little late because this occurs in September but Banned Books Week is in September. In Parkland, Florida… Remember Parkland? They celebrated Banned Books Week this year by encouraging residents to go to the city library and get a book that was being targeted by censors. If you need a reference for that, it's online. You can go to bannedbooksweek.org.

And then join me again next week. Send me your questions, topics and questions to AskDrBerry.com. I will answer those questions and bring you experts to help address those topics.

Let's not worry about the things we can't change, folks. Let's change the things we can no longer accept.